The Kunstmuseum in Basel probably represents the platonic standard of museum design. The work of a Swiss-German duo Paul Bonatz and Rudolf Christ in the 1930s, it gratifies on many levels: it is symmetrical, it is spacious, it entertains light in a way that enhances the works on display. The building also seems to contain a small joke. From the street outside it resembles the Doge’s Palace*, while inside, the courtyard is lined with high square windows and has the angular practicality of those buildings painted by Hammershoi. We move from one seat of Renaissance — and a boom period for art patronage due to the enormous transformations in finance and merchant trading power that were happening — to another; from Venice to the towns of the Hanseatic League in a few short steps.

There’s a fair amount of Swiss art inside the museum, which given the country’s unique situation, borrows heavily from both the Northern and Italian traditions.

I visited the gallery late last year. It was early evening, the sun was setting and a soft, buttery light filled the hallways. This was beautiful, even soothing, but anyone who has read my work knows that I am not particularly curious about either of those sensations, and that part of me even bristles at the manipulation of design. That isn’t to say that I cannot identify or appreciate a nice building, only that for me at least, niceness is a far as it goes.

I happened to be in Switzerland studying the history of aesthetics and the impact of one particular philosopher, Alexander Gottlieb Baumgarten. For that reason, but also just instinctively, I knew that the fulfilment of certain aesthetic criteria should never be mistaken for art. Art itself is unsettling. It is not about the mastery of form, but the often spontaneous ruptures that occur within that form and at the hands of someone who understands and respects it.

That said, one painting on the first floor of the gallery flouted so many of those rules, and was so disruptive to the calm being confected by everything around it, even I would not have chosen to display it.

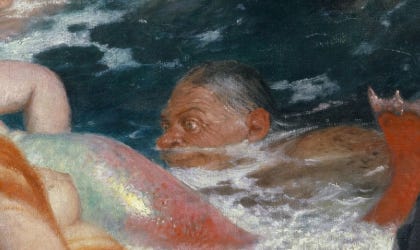

Play of the Nereides by Arnold Böcklin (1886) is two metres wide and almost as tall. In Greek mythology, the Nereids are fifty benevolent sea nymphs who often appear alongside Poseidon. Here we see just seven of them, not counting a possible baby sea nymph who is also shown clinging to a fish. I am not a classicist and would like to know if this scene is from a particular story. What I do know, is that four of the mermaids are anatomically impossible. One of them is cut off mid-fin by the edge of the painting. The rock at the centre of the image defies all laws of space. It is both cave and monolith — close by and very very far away. The only realistic element of the painting (and Böcklin is aiming for a realism of sorts, just not in his subject matter), is the lasciviousness of two men captivated by the mermaids’ sopping breasts. One of these men has a sort of Cabbage Patch quality, while the other resembles the parking lot guy from Mulholland Drive.

Where things get interesting is that Böcklin also painted Isle of the Dead (1880), a painting that is so famous and was so popular among consumers in the 20th Century, that it occupies a similar place as The Lady of Shalott (1888) by John William Waterhouse, or The Starry Night (1889) by Van Gogh. Clearly the late 1880s was a golden era for cheap prints. The fact is so well-known now that it is even mentioned in the first paragraph of the painting’s Wikipedia page (though I promise I knew it from the book :^) ), that in the 1936 novel Despair, Nabokov wrote that Isle of the Dead could be “found in every Berlin home.”

Make of this what you will, but when the French were falling over themselves to purchase chintzy Renoir replicas of sun-dappled gardens, their German neighbours were doing the same over this:

Böcklin is Swiss and actually from Basel, so that goes some way to explain why the gallery chose to display so many of his works, including those that strayed from the more austere paintings of his earlier career. Still, awe-struck by what I had seen, after leaving the gallery I messaged a friend who had lived in Basel for many years. He knew the painting well and was fond of the fearful mer-baby. “Imagine painting that,” he said. “What must be going through your head?” The answer was probably very little, or at least very little conscious thought. Böcklin was not a good painter, and his interests veered towards the cornier end of the corny Nineteenth Century. From a scan of his Wikipedia page I also found out that he would travel to Italy, making the following statement a bit of stretch; but I like to imagine that beneath the stiff formality and conservatism of Swiss society, and a landlocked nation whose large, placid lakes have never known turbulence, lurks a desire for errant bodies and crashing waves.

* I’m referring here to the leader of Venice rather than the cryptocurrency inspired department of the US government.

I just wanted to say thanks to anyone who has subscribed to this. I am working on something very long and all-consuming and this provides me with a nice distraction at the moment. I hope to update it more reliably very soon.

I would like to see this painting, the internet version cannot possibly do it justice. There is something very comical, joyful and fun about it all. The darkness in contrast to the frolick, the observance by the humans brings out the confusion and lack of comprehension on our part of mythical things...it is definately sacred and profane.

I don’t see what’s so bad about it. It looks fun and chaotic in the best way. I love that chubby lil mer-baby, she has such an overwhelmed expression that might well capture the feelings of many who see this painting for the first time